Sinochips Diagnostics, a private laboratory operating on the campus of the University of Kansas Medical Center, has tested more than 2,500 people for the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. With clients that include the Wyandotte County Health Department, it’s performing a critical service as one of 27 laboratories in Kansas running diagnostic tests for the virus fueling the pandemic.

But Sinochips Diagnostics, a KU spinout, wasn’t set up to perform these tests, at least not initially. It took some quick thinking, a large monetary donation and synergy between people and organizations to get this start-up lab, co-founded by a KU School of Medicine professor, delivering around 100 to 200 coronavirus results a day, six days a week.

From precision to pandemic

Andrew Godwin, Ph.D., is professor and director of molecular oncology in the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at KU Medical Center. He’s also deputy director of The University of Kansas Cancer Center.

is professor and director of molecular oncology in the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at KU Medical Center. He’s also deputy director of The University of Kansas Cancer Center.

But Godwin is also an entrepreneur. Fueled by the entrepreneurial spirit he says is prevalent at KU Medical Center, he sought help from a venture capitalist to start a pharmacogenomics company. And what is pharmacogenomics? It involves testing to see how drugs can affect each person differently based on genetic factors. It’s part of Godwin’s research interests in precision medicine, which seeks to discover how and why medical treatments can differ from person to person based on their genetic makeup.

That pharmacogenomic laboratory, Sinochips Diagnostics, opened in August 2019 inside the on-campus business incubator. Sinochips Diagnostics leased space in the remodeled Bioscience & Technology Business Center, which was designed to boost commercialization of KU research. The center is in in Breidenthal Hall, just down the street from the Health Education Building.

Lowell Tilzer, M.D., Ph.D., a long-time professor and the former chair of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at KU Medical Center, was selected as its medical director.

The next few months were dedicated to the time-consuming tasks to ramp up a lab – hiring staff, setting up protocols, developing operating procedures, obtaining accreditation. And then life intervened.

“The Sinochips’ staff were about to launch the validated pharmacogenomics tests,” Godwin said, “and then the COVID pandemic occurred, and we decided we needed to respond.”

Connecting with Wyandotte County

In mid-March, Godwin reached out to Allen Greiner, M.D., the chief medical officer for Wyandotte County. Greiner also is professor and vice chair of family medicine in the KU School of Medicine.

“Dr. Godwin knew that some of us in the Department of Family Medicine were involved heavily in activities at the public health department in Wyandotte County,” Greiner said. “He reached out to us by email to see if we might have a need for laboratory processing services for samples collected from community members we suspected of having COVID-19.”

At that time, Greiner said, Wyandotte County’s health department had no resources to test community members. “Within 10 days, we were collecting patient samples, and Sinochips was doing the processing of all of our tests.”

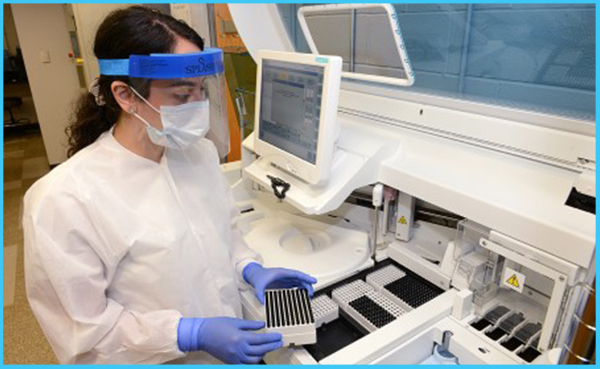

Those 10 days were busy ones at Sinochips as they redesigned the lab and retooled their protocols. Godwin said a private benefactor provided the $150,000 for the new equipment necessary to run the tests that detect COVID-19.

Adding clients

From there, Sinochips’ client list grew. Adam Pessetto, operations manager for Sinochips Diagnostics, said the lab provides service to “safety net” clinics such as Vibrant Health, a group of three neighborhood clinics in Wyandotte County offering health services to the community on a sliding scale, and to the Linn County (Kansas) Health Department.

From there, Sinochips’ client list grew. Adam Pessetto, operations manager for Sinochips Diagnostics, said the lab provides service to “safety net” clinics such as Vibrant Health, a group of three neighborhood clinics in Wyandotte County offering health services to the community on a sliding scale, and to the Linn County (Kansas) Health Department.

Additionally, Sinochips performed 502 tests for a clinical trial at the KU Cancer Center. Cancer patients were provided with free COVID-19 tests if they opted into a study and agreed to have their treatment plan tracked should their test be positive.

During the early weeks of testing, the lab averaged 100-150 tests a day, then dropped to 30 a day when the laboratory at The University of Kansas Health System began performing more COVID-19 tests. Tests now number 100-200 a day. “Word of mouth continued to spread, and requests for testing support increased,” Pessetto said. Lab capacity could be up to 300 a day with no reconfiguration and up to 1,000 a day with a new, but more costly, configuration, he said.

Godwin said the Sinochips’ staff are dedicated, no matter how many tests they’re running. “They work very late into the night to ensure that the results are ready the next day,” he said.

About the tests

Sinochips initially used a test called real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR). A health care worker uses a nasal or nasopharyngeal swab to collect the patient’s secretions from either the nose or the back of the throat. Then, through a series of steps, the RNA in the sample is converted and copied to see if the virus is present.

“This test is highly reliable in the hands of trained personnel but still an art,” Godwin said, because of the complexity in securing representative samples and in validating the accuracy of the test.

Sinochips technicians met the person delivering the swabs outside the building. The exterior transfer meant only trained Sinochips personnel handled the potential biohazard inside Breidenthal Hall, Godwin explained, to protect other workers in the building.

When Sinochips first began testing in March and early April, a whopping 23 percent of all tests came back positive. That rate was more than double the percentage of positive cases reported by the Centers for Disease Control at that time, but it’s closer to the percentage of all national tests since.

“We were providing testing for those that had the more severe symptoms, so we were expecting to see a fairly high percentage of positivity,” Godwin explained.

The lab now uses an antibody test, also referred to as serology testing, which uses a small blood sample instead of a nasal swab.

“I think (the antibody test) is going to be the crucial next step, because as we have over 3.3 million individuals in the U.S. who are positive (for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19), we’ll find that there are many more carriers who never showed any severe symptoms,” Godwin said. “Somewhere along the way, we want to be able to identify those individuals to help estimate how many people in the U.S. have been infected and to understand why they were more immune to the effects of the virus.”

Providing for community

Godwin said he recommended retooling Sinochips Diagnostics to run COVID-19 tests because the community – his community – needed help.

Moreover, the lab runs the tests “at cost.” “I’ve always been very passionate about helping the underserved,” Godwin said. “I reached out to Allen because we knew a lot of people in the community were not getting care, and they and the State of Kansas were getting way behind in testing.”

Greiner said Sinochips Diagnostics also has been able to save money for Wyandotte County. “Many other local and regional labs have not been able to offer an at-cost test price, and we are extremely fortunate to have this connection with Dr. Godwin and his company.”

Greiner called the synergy “translational science at its best,” where the discoveries of basic science are transferred to a community for the greater good.

“I think the partnership between the Wyandotte County public health department and Sinochips is a great example of how the University of Kansas Medical Center entrepreneurship can make an impact on the health and well-being of a local community.”